Friday Prayer at the Great Mosque of Djenné: Islamic Architecture and Communal Ritual in Mali

Published on: April 17, 2025

In the heart of Mali, among the winding arms of the Bani River, stands the Great Mosque of Djenné, a monument born from the earth itself. Its walls, sculpted from sunbaked mud bricks known as ferey, rise like a golden mirage above the bustling market plaza. This mosque is not merely the centerpiece of Djenné but the beating heart of Islamic tradition and communal life for thousands of West African Muslims.

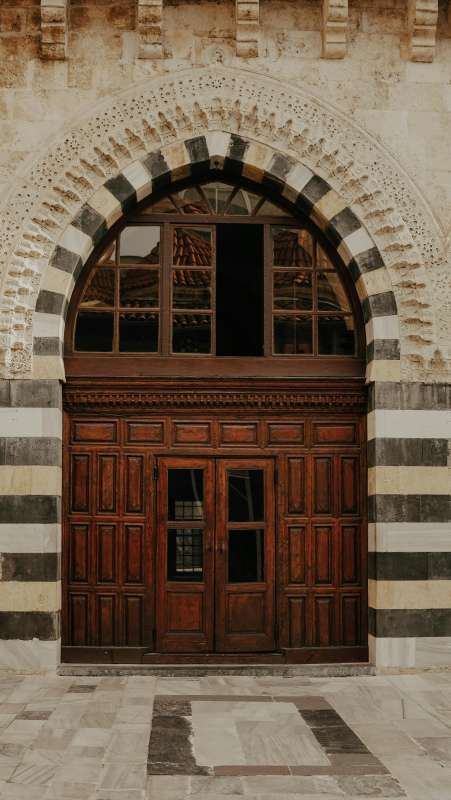

Constructed originally in the 13th century under the first conversion of Djenné’s ruler, Koi Konboro, to Islam, the mosque has undergone cycles of destruction and restoration, reflecting epochs of war, colonialism, and resilience. Its current form, completed in 1907 under French colonial administration with local masons and traditional techniques, stands as the largest mud-brick structure in the world and a UNESCO World Heritage site. The mosque emanates the Sudano-Sahelian architectural style, characterized by thick, tapering walls, wooden beams called toron that serve both as support and as ladders for annual replastering, and dramatic minarets crowned by ostrich eggs, a symbol of fertility and purity in local cosmology.

Friday Prayer: The Rhythms and Rituals of Jumu’ah

Every Friday, as noon approaches, Djenné transforms. From each slender alley, boys run with woven mats tucked under their arms, elderly men stroll in bright boubous, and the call to prayer, adhan, floats over the rooftops. The pulse of the city quickens as merchants wind up their trading, dust settles, and anticipation thickens like the mud clay itself. The mosque’s courtyard and prayer hall—designed to hold over 3,000 worshippers—swells as the faithful gather for jumu'ah, the communal Friday prayer considered especially blessed in Islamic tradition.

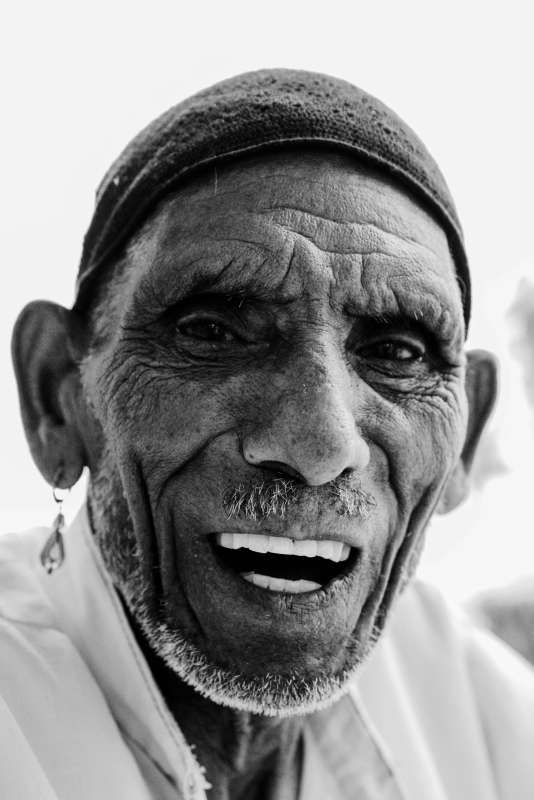

Imam Boucoum, who has led prayers for decades, describes the sacred resonance: "On Fridays, we do not merely recite the khutbah and pray; we gather our histories, our struggles, our hopes. The mud walls remember every echo of our voices, every dream spoken in silence." The prayer service, conducted in Arabic but woven with local Songhai, Fulani, and Bambara expressions, is followed by community announcements and blessings.

For many, the act of worship at Djenné transcends religious duty—it affirms their connection to a lineage stretching back to the earliest days of Islam’s arrival in West Africa. According to Malick Diabaté, a scholar and mosque caretaker: "My father and his father prayed here. The same earth beneath us, the same sun above. The mosque is our bridge between generations."

Islamic Festivals: Community Life Around Ramadan and Maulud

The rhythm of Djenné’s spiritual calendar is marked not only by weekly prayers but by vibrant celebrations of Ramadan and Maulud (the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday). During Ramadan, the mosque becomes both sanctuary and stage:

- Pre-dawn and sunset meals (suhur and iftar) are shared among hundreds, with older women distributing millet porridge and dates beneath the mosque’s colonnades.

- The bottom of the minarets flicker with oil lamps at night, and groups gather for taraweeh (special nightly prayers), filling the air with communal recitation and songs.

- On Laylat al-Qadr, the "Night of Power", young boys stay awake until dawn reading Quranic passages, believing that the entire city is enveloped in divine blessings.

Maulud transforms Djenné into a theater of devotion:

- Processions swirl through the ancient streets, with Islamic scholars leading crowds in chanting praise-poems for the Prophet.

- Special lessons (madrasa) and public feasts are held, blending Islamic teachings with local storytelling and music.

These festivals are vital moments of intergenerational transmission, teaching children the stories of the faith while embodying the enriching syncretism of Malian Islam—a blend of Quranic orthodoxy, Sufism, and local custom.

The Community and the Care of the Mosque: The Annual Crépissage

Perhaps the most remarkable tradition connected with the mosque is the annual Crépissage de la Grande Mosquée, or re-plastering festival, which occurs every May after the first heavy rains. As the mud plaster erodes due to weather, thousands unite to restore the mosque, layering it anew with a mixture of clay, rice husks, and water from the river. Men, women, and children all participate, turning arduous maintenance into a joyous event full of song, drumming, and friendly competition between neighborhoods.

As told by Aissatou Cissé, a life-long resident of Djenné: "As a girl, I would help fetch water from the river. Now my sons race up the scaffolding with buckets. We care for the mosque like it is our home—if a crack appears, the entire city feels it. The annual repair is not only work; it is worship and festivity."

Sudano-Sahelian Architecture and Its Symbolism

The distinctive architecture of the Great Mosque is not simply a question of aesthetics—it encodes religious and cosmological meanings. The three massive towers or minarets symbolize the three principal leaders of Djenné’s Islamic community. The wood toron beams jutting out from the walls give the appearance of a living, breathing organism. In the words of Oumar Sangaré, a local mason: "These beams are the mosque’s arms. They reach to heaven, but also invite us to climb, to care for what God has given. Every beam, every mud brick, is the work of many hands."

The mud itself is a spiritual material: ephemeral, needing constant care, yet rich and fertile. The choice of ostrich eggs to top the towers is both a protective charm and a symbol of unity across Mali’s diverse peoples.

Women and the Mosque: Invisible Pillars

Though tradition designates specific spaces for men and women during prayer, the role of women is unmistakably central. They lead in organizing festivals, preparing communal meals, teaching Islamic morals, and raising funds for mosque upkeep. Djenné women are renowned for their mastery of indigo dyeing and textile arts, which are exhibited in new garments for Ramadan and Maulud celebrations. According to Fatoumata Sidibé, a local matron: "Even when we are not in the front row of prayers, we are the prayers’ heart. We build faith in our children, we keep the walls strong with our labor and our love."

The Marketplace and Mosque: A Symbiotic Relationship

The mosque’s role as a religious center cannot be separated from its economic and social importance. Djenné’s marketplace—the largest in the Inland Delta of the Niger River—unfurls every Monday in front of the mosque, attracting traders from hundreds of kilometers. Islamic values of fairness, charitable giving (zakat), and honest trade infuse the commerce. Many deals are finalized with oaths "by the mosque," and disputes are often settled by the imams after prayer.

As one market trader put it: "Without the mosque, there would be no market; without the market, there would be no mosque. They feed each other, like the river and the fields."

Conservation, Challenges, and Global Significance

Despite its enduring presence, the mosque faces increasing threats: erratic rains due to climate change, erosion from flooding, political instability, and the encroachment of modern building materials. International bodies like UNESCO have provided funding, but it is the local rituals—especially the annual créppisage—that have proved irreplaceable in preserving both the structure and the spirit of Djenné.

Some younger residents question the relevance of traditions in a changing world. Yet, as age-old cycles repeat each Friday, and during every festival, the community reaffirms its commitment to both faith and heritage. The Great Mosque of Djenné remains, above all, a permanent testament to a living, evolving Islam rooted in African soil.

Anecdotes and Living Memory: Oral Histories

Personal histories add a vital human dimension to these traditions. Moussa Samaké, now in his seventies, recalls his childhood in Djenné: "As a boy, I would wake before dawn every Friday. My grandfather would wash at the small well behind our house with water he said was as old as the city. He would put on a white robe, and we would walk slowly to the mosque, passing neighbors who greeted us in Arabic and Bambara. After prayer, he would remind me that building the mosque is like building your life—layer upon layer, always renewing what the rains have softened."

Today, such stories fuel the collective memory of Djenné and inspire youth to continue the uniquely local blend of Islamic ritual, craftsmanship, and community pride that defines this remarkable city.

Selected References and Additional Resources

- UNESCO: Old Towns of Djenné

- Britannica: Great Mosque of Djenné

- Archnet: Djenné Mosque

- National Geographic: Rescuing Africa's Greatest Mud Mosque

Through the centuries, the Great Mosque of Djenné endures not only as the world’s largest mud mosque, but as a living school of faith, craftsmanship, and communal memory—a monument shaped by hands, held together by prayer, and renewed each year by the very people it serves.